The theme of this year’s World Environment Day (5 June 2018) is Beat Plastic Pollution. Plastic pollution is indeed a serious problem, severely affecting animals, humans, and marine ecosystems. Removal of the pollutants that are already in the environment is exceedingly difficult, so we should also ask: How can we avoid plastic and other pollutants entering the environment in the first place?

The theme of this year’s World Environment Day (5 June 2018) is Beat Plastic Pollution. Plastic pollution is indeed a serious problem, severely affecting animals, humans, and marine ecosystems. Removal of the pollutants that are already in the environment is exceedingly difficult, so we should also ask: How can we avoid plastic and other pollutants entering the environment in the first place?

Year: 2018 Page 3 of 4

Abraham Lincoln said: “If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong”. Similarly we could say: “If the abolition of slavery is not an instance of moral progress, then nothing is an instance of moral progress.” The abolition of slavery is the favourite example of philosophers who write about the topic of moral progress. While the existence and the possibility of moral progress are contested, the view that if there were such a thing as moral progress, the abolition of slavery would be an instance of it is not. (By the way, I fully acknowledge that slavery still exists, especially new forms of slavery, which are in some respects even worse than the old forms. But this doesn’t change the fact that the slave trade that we used to have for centuries is now illegal in every country in the world.) Other popular examples of moral progress include the development of a human rights regime, the emancipation of women and the abolition of foot binding. In a previous post, I argued that moral progress is not impossible and cited evolutionary considerations. In this post, I challenge Michelle Moody-Adams’ view of moral progress in social practices as the realization of previously gained moral insights.

With significant recent advances in artificial intelligence and robotics, it is increasingly pressing that we consider the legal and ethical standing of autonomous machines.

Here I post some considerations on this matter from a recent debate organised by Thomas Burri (University of St. Gallen) with Shawn Bayern (Florida State University) and myself:

In this post, I explore the punitive justifications for the recent strikes against Syria in response to the alleged use of chemical weapons. In the previous post, Sara was right to call into question the HI justification for the strikes provided by Theresa May. Indeed, even if one could assume that the strikes could satisfy the just cause criterion (and this is a big if), it’s doubtful that other ad bellum criteria could be met (proportionality and reasonable chance of success). The situation is Syria is complicated with multiple parties involved, either directly or through proxy. It is, therefore, difficult to determine what success would mean in this context and, correspondingly, what would be counted as proportionate force. I think Sara is right that the strikes could not be justified on the basis of HI. But, I ask, are there any other justifications for these strikes?

Early on Saturday, 14 April, it was announced that the US, UK and France had conducted targeted strikes on three targets in Syria – a chemical weapons and storage facility, a research centre and a military bunker – in response to Assad’s (alleged) use of chemical weapons in Douma. The reaction to this news was mixed. One key problem that was highlighted was the question of the legality of the strikes, under both domestic and international law. However, although these are of course very important issues, a different one has remained relatively unexplored: could these strikes be permissible from a moral perspective? Given that international law is largely customary, and given that law doesn’t exhaust the limits on our behaviour, this is a crucial question.

There are a number of ways in which the resort to strikes on regime targets in Syria could be justified. The common moral framework for thinking about the morality of war, just war theory, recognises a number of reasons for legitimate use of force: self-defence against aggression, defence of another state against aggression and, increasingly, intervention to alleviate humanitarian suffering. In this post and the next, Anh Le and I will consider whether the strikes could be justified according to the standards set by just war theory. Here, I will consider possibly the most controversial just cause: intervention in order to stop severe suffering. In the next post, Anh will investigate whether the strikes can be considered morally legitimate as forms of punishment.

Last year, Kevin C. Elliott published three new books on ‘values in science’:

Given that empirical research is often used by moral, social, and political philosophers in scholarship on questions of justice, we thought it would be interesting to chat to Kevin about his recent work and its implications for moral, social, and political philosophy.

As the readers of this blog probably already know, UK-based academics have been on strike for five days over the past two weeks, and the industrial action is likely to escalate further. The current dispute concerns pensions, is quite major, and many good things have been written about it – including, and indeed especially, by other political theorists.

The question I would like to address here has less to do with the specifics of the current dispute and more with a general point that circulates among fellow-academics – and philosophers in particular – nearly every time the possibility of a strike is raised: are we, as comparatively privileged workers, justified in striking to keep and sometimes even improve our privileged status? The point is made in a particularly forceful manner when strike for pay is at stake, but is actually equally relevant to pensions – after all, UK academics are currently striking to defend their current defined benefit pension plan, and the very fact of being in a defined benefit pension scheme (even if one whose conditions have worsened over time) is a rare luxury these days.

Over the last two weeks, I have myself been suspiciously quiet about the fact that I am on strike in many of my daily interactions. This is especially the case with people who might reasonably regard my being on strike as a luxury – such as the carers at my daughter’s nursery, who are on minimum wage, do not get sick pay, and could not even dream of being in a union. That is, I feel self-conscious not only about what I am striking for, but about the very fact of being on strike: just that, in itself, feels like a privilege.

And yet I have little symapathy for the argument that academics should not strike; indeed I believe that too much self-reflection on our relatively privileged status is a display of complacency rather than virtue.

So, why do the comparatively privileged have a claim to strike?

- Because it’s either us or nobody else. The practice of withdrawing labour comes well before the establishment of the right to do so within a framework of labour law: the first strikers were engaging in industrial action at their own risk. Then, at least in Europe, strike has (fortunately) become a right. In so doing, it has come to be perceived as something that requires certain some guarantees to be in place: strong union-friendly legislation, the guarantee that one will not lose one’s job over industrial activity, etc. But as labour standards – after a steady improve over the golden era of the welfare state (apologies for the oversimplification) – have been deteriorating again in OECD countries over the last decades, this right has become less of a universal guarantee and more of a privilege of the few who still enjoy a permanent and secure contract, robust labour guarantees, the luck of working in strongly unionized sector, etc. If you come to see something as a right (and rightly so, don’t get me wrong!), then something is obviously problematic when only some enjoy it, and on arbitrary grounds at that. The question of whether those privileged few should exercise a right which others are deprived of has some prima facie legitimacy. But we are not doing atypical and vulnerable workers any favour by not exercising our right to strike. We are only actively contributing to erasing striking from the toolkit of progressive politics. If the very idea of striking is to stay alive, the last thing to do is tell those who can still strike relatively safely that it is bad taste of them to do so. Of course, we want to find ways of enabling those who are even much more vulnerable than us to engage in industrial action again, and this is a tricky task to say the least – but making industrial action a vestige of the past is certainly not a sensible way of achieving said aim.

- Because the benefits we would be giving up on would exacerbate, not mitigate, inequality. Yes, the demand for a pay increase that reasonably follows the trajectory of growth and inflation, and for keeping a defined benefit pension scheme, are a privilege of the few these days. But we all know perfectly well that we are not being asked to give up on those in order to redistribute down. By refusing to resist, we would only contribute to making inequality steeper.

- Because it is about relational goods. For decades now, academics have been asked again and again to do a little bit more, a little bit better, for a little bit less – and often with no good justification. Whether or not there are workers whose conditions are incomparably worse, this is not a way to treat people in the workplace and ought to be resisted, period.

- Because it is about showing disobedience, defiance and will to fight back. UK universities are increasingly run like businesses, with all the problems that this entails – short termism, disregard for the specific nature of higher education, job insecurity, hierarchy in decision-making, and the treatment of staff as disposable goods being only some of them. Those of us who can still do so without bearing prohibitive costs should simply engage in all the push backs they can. The idea that workers should just shut up, get their heads down, and get s%&t done must encounter resistance.

Are there other reasons why the comparatively privileged should strike? Or are there other, stronger objections to the right of the relatively privileged to strike which deserve a fair hearing?

This is an interview with Isabelle Ferreras, who has just published a book on workplace democracy – to my knowledge, it’s the most detailed argument and proposal for a specific form of workplace democracy that has been provided in recent years. To get a sense of what it is all about, check out the animated trailer at www.firmsaspoliticalentities.net. We asked Isabelle to tell us more about her book, and we are very happy that she immediately agreed to do so.

Q: How did you get interested in the topic of workplace democracy?

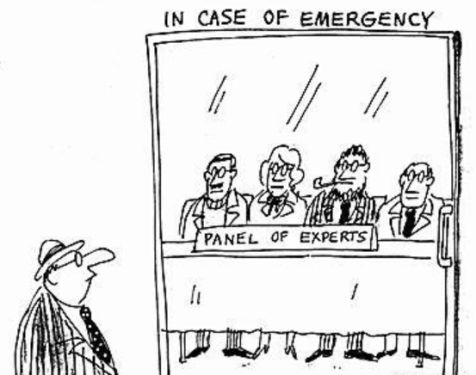

Why do we trust experts to take care of our health and not to take care of our interests in the political realm? This is a very old question of democratic theory. Epistocracy is a neologism frequently used in recent works to refer to a form of government by those who know more or are wiser than the mass.

Two different aspects might differentiate an epistocracy from a democracy: the absence of political equality in the selection of the rulers, or the absence of egalitarian accountability. In addition to these undemocratic aspects, an epistocracy would differ from other non-democratic regimes by some mechanism allowing people who distinguish themselves from the mass by their wisdom or expertise to rule or at least enjoy an important degree of political power. The best example and – to my knowledge – the most interesting challenge to our democratic convictions is Jason Brennan’s idea of an “epistocratic council”. Members of this council would be selected on a meritocratic basis, passing a competency exam. And all citizens would have an equal voice in the choice of the expertise criteria.

Leaving aside the practical challenges such as the choice of the people in charge of preparing the exam, what would be wrong with such an epistocratic council?

For the past few weeks, people on- and offline have spoken up to question Winston Churchill’s legacy. They generally highlight his racism, his support for the use of concentration camps, his treatment of Ireland, his complicity in the Bengal famine, and more. Some protested in a Churchill-themed café. In response, others argue that he nevertheless deserves to be remembered for his role in fighting off the Nazis and inspiring the British public in dark times. There are, however, important questions to ask even about Churchill’s role in fighting the Nazis. Churchill authorised the indiscriminate killing of civilians by bombing German cities. In justifying this tactic, Churchill appealed to the extraordinarily dangerous nature of the situation. But does this justify indiscriminate killing? This question still has relevance today. US drone strikes in the Middle East and Afghanistan in many respects resemble a campaign of indiscriminate violence, and so it is necessary to ask if this campaign can be justified. I will here argue that the logic of Churchill’s defence does not, and indeed cannot, justify the use of indiscriminate violence.