What’s wrong with an epistocratic council?

Why do we trust experts to take care of our health and not to take care of our interests in the political realm? This is a very old question of democratic theory. Epistocracy is a neologism frequently used in recent works to refer to a form of government by those who know more or are wiser than the mass.

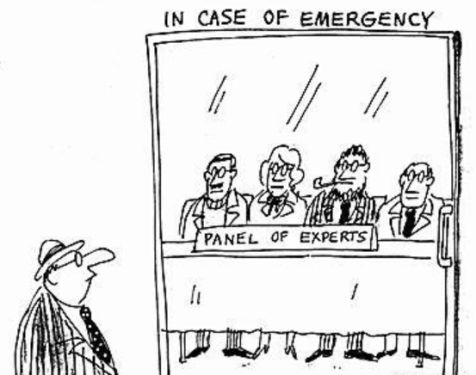

Two different aspects might differentiate an epistocracy from a democracy: the absence of political equality in the selection of the rulers, or the absence of egalitarian accountability. In addition to these undemocratic aspects, an epistocracy would differ from other non-democratic regimes by some mechanism allowing people who distinguish themselves from the mass by their wisdom or expertise to rule or at least enjoy an important degree of political power. The best example and – to my knowledge – the most interesting challenge to our democratic convictions is Jason Brennan’s idea of an “epistocratic council”. Members of this council would be selected on a meritocratic basis, passing a competency exam. And all citizens would have an equal voice in the choice of the expertise criteria.

Leaving aside the practical challenges such as the choice of the people in charge of preparing the exam, what would be wrong with such an epistocratic council? (more…)