To Strike or Disrupt? (take 2)

In November and December 2019, members of the University and College Union (UCU) – the trade union that represents many academics and other university staff in the UK – went on strike. On that occasion, in his post To Strike or Disrupt, Liam Shields discussed whether people not doing any teaching during the strike should go on strike or not, seeing that their striking does not result in significant disruption.

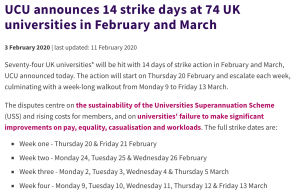

At the end of this week, the UCU will embark on a new wave of 14 days of strike spread over four weeks because the dispute remains unsettled. It therefore seems a good occasion to recall Liam’s argument and to flesh out some implications a bit further.

Why does the UCU go on strike?

To briefly recapitulate, at the centre of the dispute are two issues.

The first concerns changes in the pension scheme, which will result in people paying more in to their pension, but receiving less out of it.

The first concerns changes in the pension scheme, which will result in people paying more in to their pension, but receiving less out of it.

These issues are important for all members of university staff, but especially for members of minority groups and people on temporary or part-time contracts.

Causing disruption on non-teaching days

Should people (on permanent contracts) who are on research leave or who will not be doing any teaching on some or all strike days go on strike? Or should they rather work as required by their contract and donate the salary that they receive on these non-teaching days to the Fighting Fund to help support those who might not be able to afford to strike without it?

In his post, Liam invoked the principle of maximising disruption to make sense of this. The assumption is that disruption of normal proceedings will incentivise employers to give in to the UCU’s demands. Withdrawing one’s labour on teaching days does indeed cause clear disruption: students do not get the teaching session they have paid for, release of marks and feedback is delayed, …*

In contrast, the suggested working-and-donating on research days rests on the assumption that withdrawing one’s labour on research days does not cause much disruption.**

However, is this really the case? Research is part of our job and most of us have targets regarding publications or grant capture, so doesn’t withdrawing one’s labour on research days cause disruption similar to not delivering teaching? The issue is that research targets are often much vaguer, longer-term and less tangible goals. Delaying research for the period of the strike therefore causes almost no – or difficult to measure – disruption to the university. This is vastly different from not teaching a particular lecture on a particular day or delayed release of marks, which does cause tangible (but regrettable) disruption.

Instead, as Liam argues convincingly in his original post, working-and-donating on research days makes it possible for others to go on strike, and thus increases disruption. Indeed, it promotes the capacities of colleagues in precarious positions (for example, temporary staff or teaching assistants paid by the hour) to exercise their right to strike. So following the principle of disruption, it makes sense to work during days devoted to research and to donate one’s pay.***

The symbolic value of going on strike

People (on research leave or on research-only contracts) who do not do any teaching at all during the strike period have an additional worry, though: working-and-donating rather than going on strike would not record their opinion in the dispute.

First, they may be worried that official statistics will register them as not striking at all, and so their support for the union and opposition to the position of the universities will go unnoticed when one works-and-donates. Luckily, there is a relatively easy fix here: they can join the strike for one or two symbolic days and record it as such afterwards. This slightly diminishes the funds available to support colleagues who would otherwise not be able to strike, but I believe that the benefit of having an additional name in the statistics outweighs this cost.

Second, in his original post, Liam states that solidarity requires some sacrifice, and since working-and-donating involves sacrifice, it can be considered in line with the requirements of solidarity. However, as mentioned by Pierre-Etienne Vandamme’s comment to Liam’s post and in Liam’s response to it, there may be symbolic value in joining colleagues at the picket line, including the values of mutually supporting colleagues and increasing the visibility of the strike by joining the picket. Since donating to the Fighting Fund helps others (who might otherwise be unable to join the strike) to go on strike, I don’t think this is a very powerful objection. Moreover, striking for a few symbolic days may further reduce its force. But we can think of additional means to support colleagues, for example by making one’s intention to work-and-donate public, sending supportive messages to colleagues, bringing coffee to colleagues at the picket, …

A final worry, in a slightly different way related to the symbolic value of going on strike, is that working-and-donating instead of going on strike may require someone to cross the picket line. When research can be done from home, this does not pose a problem. However, often research will require access to a lab or other resources only available on campus. In these cases, again, it would be important to communicate clearly one’s intention to support the strike by donating to the Fighting Fund.

All of this, I would say, takes most of the sting out of the objection that working-and-donating might erode the symbolic value of going on strike.

Conclusion

Whether or not to join the strike is of course a personal decision. This post just teases out some implications of and addresses some worries regarding the principle of disruption as an argument for working-and-donating rather than going on strike on non-teaching days. Having considered these issues, I believe that the rationale remains sound.

I’m grateful to Liam for his insightful comments, as well as to some colleagues for helpful discussions. Any remaining errors in the opinion above are mine.

Notes

* To be clear: disruption is (and should be) a last resort when other means have been exhausted in the negotiations over disputes between employers and employees. People on strike in general regret the disruption they cause, especially the impact on students. Helpful guidance and resources for students regarding the strike action are provided by the National Union of Students on their website.

** Administrative responsibilities are much trickier. Disruption to a large degree depends on one’s particular admin role. In some instances, withdrawing one’s labour can have a very disruptive effect on university proceedings. In other cases, disruption will be limited. Often admin tasks happen in between other stuff; some admin roles involve specific tasks and tangible targets (for example, Plagiarism Officer), while others don’t (for example, revamping a programme or promoting equality and inclusivity in one’s Department); and withdrawing one’s labour regarding admin often means that one has to deal with it after the strike under increased pressure or time constraints. On the other hand, even if one is not on strike with respect to administrative responsibilities, the tasks involved may be hindered by the fact that colleagues are on strike. The principle of disruption does not seem to give a uniform answer regarding administrative responsibilities.

*** As a side note, it would not be helpful to spend days devoted to research or days in between strike days catching up on emails or in other ways dealing with the fallout of the strike beyond what would be expected on such days. This would be counterproductive because it would erode the disruption one caused just the day before. The principle of disruption would here recommend to work to contract on these days and to spread one’s time across teaching, admin and research according to how one has scheduled these in line with one’s contract.