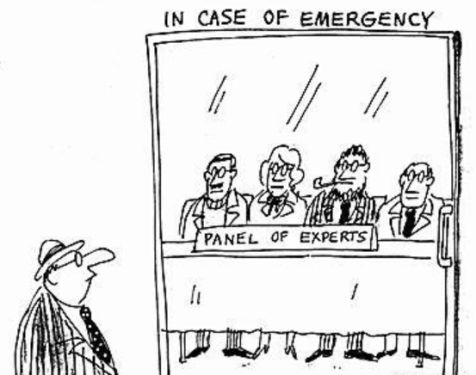

What’s wrong with an epistocratic council?

Why do we trust experts to take care of our health and not to take care of our interests in the political realm? This is a very old question of democratic theory. Epistocracy is a neologism frequently used in recent works to refer to a form of government by those who know more or are wiser than the mass.

Two different aspects might differentiate an epistocracy from a democracy: the absence of political equality in the selection of the rulers, or the absence of egalitarian accountability. In addition to these undemocratic aspects, an epistocracy would differ from other non-democratic regimes by some mechanism allowing people who distinguish themselves from the mass by their wisdom or expertise to rule or at least enjoy an important degree of political power. The best example and – to my knowledge – the most interesting challenge to our democratic convictions is Jason Brennan’s idea of an “epistocratic council”. Members of this council would be selected on a meritocratic basis, passing a competency exam. And all citizens would have an equal voice in the choice of the expertise criteria.

Leaving aside the practical challenges such as the choice of the people in charge of preparing the exam, what would be wrong with such an epistocratic council? It would not necessarily deprive people of the opportunity to participate in collective decisions more than representative democracy does. Depending on the powers of the council, people might still have the opportunity to elect the executive or the legislative, and they would have the chance to participate to the definition of the required competencies to serve in the council. Advocates of direct democracy will consider this as insufficient, but for advocates of representative democracy, the task is more difficult.

Some might object to it on proceduralist grounds, arguing that democracy is a matter of equal status and that the competency exam fails to acknowledge this equal status. What I am interested in is figuring out whether epistocracy can be objected to on epistemic grounds. Is it the case that it would make better decisions than standard democracies?

In order to answer this question, we need a standard of good decisions. In the paper I am writing, I argue that two criteria of good decisions should not be controversial: rationality and impartiality. Whatever the ultimate goal that we would like politics to pursue, I think we can all agree that these two qualities matter. Rationality, understood in an instrumental sense, refers to the capacity of a decision making system to select the appropriate means for the ends pursued. Whether we want peace, prosperity or justice, we will all agree that it matters to be able to identify the best ways to pursue our aims.

Impartiality, understood in a moral sense, refers to the norm of giving an equal importance to each citizen, of not favoring some over others. The idea is that the fundamental interests of no one should receive higher importance. Ideally, no one should have fewer rights, fewer opportunities, enjoy a lower status or receive less respect from the state. This is what the moral norm of impartiality requires. Although the means to pursue such ideal are extremely controversial, this fundamental moral requirement lies at the core of most modern ethical theories.

Let us assume, for the sake of the argument, that an epistocratic council would offer better prospects of instrumental rationality. This would not suffice to build a case in its favor, as we also need to take into account moral rightness, or impartiality.

What would be the prospects of impartiality with an epistocratic council? I see two main problems. The first is the risk of voluntary misrule: decision makers advancing their own interests at the expense of others. This comes from the lack of egalitarian accountability. Because accountability is deficient in existing democracies, this problem affects them as well, but we can easily imagine things being worse without any mechanism of accountability. Education, expertise in the social sciences and political philosophy, or any other cognitive criteria that might be selected for the competency exam will not guarantee moral impartiality. And even if impartiality is recognized as a decisive criterion to serve in the council, it cannot be appropriately tested for it can be fainted and cannot be considered as a stable disposition acquired once and for all.

The second risk is involuntary misrule, or biased decisions. Even if we assume that rulers are willing to make impartial decisions, there would be more important risks of misrule in an epistocracy because of the lack of inclusion. Besides generating some accountability, elections and political parties also institutionalize a feedback mechanism that imperfectly allows information to circulate from the masses to the rulers and back. Especially when they are accompanied by public debates, elections and campaigning by political parties send signals and information that may be lacking in an epistocracy. Members of an epistocratic council may be very well educated and disinterested; they may end up more biased because they would not have the electoral incentives to listen to the signals stemming from civil society. And this worry finds support in the literature on situated knowledge. Granted, epistocrats aware of this epistemological problem might organize public consultations, but there would nonetheless be an important risk that they would rather trust their own knowledge – the reason why they were selected. From this viewpoint, getting rid of the democratic principle that all major citizens should be the ultimate sources of the law is a dangerous epistemological move.

When assessing the epistemic potential of an epistocratic council, we are then in a situation where it could offer better prospects of instrumental rationality, but worse prospects of moral impartiality. How should we arbitrate this trade-off? The important thing to see is that the value of instrumental rationality is derivative. It matters because it improves our chances to appropriately pursue the aims we value. So it is these aims that should take priority. By contrast, moral impartiality is an end in itself, as prosperity or civil peace for example. Hence, the arbitration between rationality and impartiality should be clear: the means are subordinated to the end.

Nevertheless, conflicts will inevitably occur regarding the ends that should take priority. Suppose that epistocratic institutions offer better prospects of prosperity, and democratic institutions better prospects of justice. What should we do? I’m afraid the only possible answer is that for all those who agree with Rawls that “justice is the first virtue of social institutions”, the idea of an epistocratic council will be less appealing than standard democratic institutions, however defective they are, because the latter nevertheless offer better prospects of justice as impartiality.

Thanks for this post, this is such an interesting and important topic! I found myself wondering, at the end of your post, whether the Rawlsian line could also be taken a bit differently. Assume – for the sake of argument – that some epistocratic council could help improve the economic system such that the worst-off would benefit enormously. Could that give more weight in favor of epistemocratic councils? I’m in favor of your conclusion, overall, but it would be important to take on this challenge, I guess!

And one other thought that occurred to me: one real-life example are central banks, which are run by technocrats. And some recent work on finance (by Peter Dietsch, Martin O’Neill and others) criticizes them for being insufficiently impartial, in the sense that their policies after 2008 have disproportionately benefitted the rich. So that would be an interesting test case for your paper!

Thank you Lisa. A strict Rawlsian could I guess reject the epistocratic council in accordance with the priority of the first principle (if not on grounds of equal basic liberties, maybe in reference to self-respect). But the scenario you imagined would be a powerful challenge to the lexicographic priority!

Central banks are indeed a good example of an epistocratic institution – and a good illustration of the fact that political independence does not guarantee impartiality. The main difference with Brennan’s proposal is that people did not have a say in the definition of the required competencies for working there. Hence central banks are more elitist than his epistocratic council would be. But you’re right: it is still an interesting test case. The European Commission would be another. And constitutional courts, although their power is narrower.

Yes,sorry I wasn “t entirely clear. I didn”t mean to imply that in virtue of having kids I gained some special awareness of why impartiality was possible. Rather, I gained an awareness of just how large the difference is between the kinds of impartial moral theories I find intellectually most compelling and my new gut” moral instincts. I think the reference to standpoint epistemology may be misleading in that it implies I came to some true view on impartiality which I lacked before. Rather, I came to see the shape of a problem in a way I never had done before. 3 3 Report

Yes,sorry I wasn “t entirely clear. I didn”t mean to imply that in virtue of having kids I gained some special awareness of why impartiality was possible. Rather, I gained an awareness of just how large the difference is between the kinds of impartial moral theories I find intellectually most compelling and my new gut” moral instincts. I think the reference to standpoint epistemology may be misleading in that it implies I came to some true view on impartiality which I lacked before. Rather, I came to see the shape of a problem in a way I never had done before. 3 3 Report

As always little common sense has been applied in the arguments offered. Surely any epistocracy should be subjected to certain guidelines / constitution. For instance a epistocracy might have its remit to provide for all citizens certain rights with a minimum standard for the needy in terms of welfare and pay. Other factors such as social cohesion and inequality are important but should draw the readers mind to the difficulty of human beings ever agreeing on a set of common policies.

as our technological capability has reached a point where large scale destruction and planetary demise can (if not already are) happening it is time to lobby for a world council to form an accountable epistocracy.

Unfortunately this is unlikely and it is my contention we could well be within decades of total disaster. Human beings do not care.

Chris